It’s hard to recall a film being greeted with more perplexity than Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis. A production that has been 40 years in gestation, cost US$120 million, and failed to attract support from the major studios, it’s like no movie ever made. As the director is one of Hollywood’s all-time greats it seemed incredible that nobody would get on board - but after sitting through 138 minutes of this exhausting, incoherent pageant, the whole thing felt more confusing than ever. What was Coppola thinking? Hell, what was he smoking?

The self-conscious grandiosity of Megalopolis has led some critics to hail it as a misunderstood masterpiece. With the entire film bathed in a golden glow, it’s an amazing feat of visual pyrotechnics, but almost everything else has gone missing in action. The plot is a mash-up of Roman history filtered through the lens of a Hollywood B-movie, with Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) hovering somewhere in the background. The wardrobe department has engineered a schizophrenic crossbreeding of contemporary fashion with Roman togas, capes and diadems. The script is a collage of quasi-philosophical banalities and quotations from Shakespeare, Marcus Aurelius, and allegedly Plutarch and Ovid. The acting is as stilted as one might imagine with such a script, or completely over-the-top.

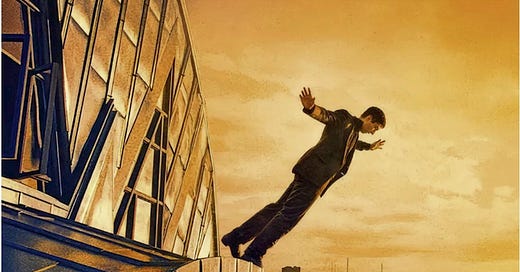

I watched this film in a kind of trance, wondering how weird it could get, and for how long Adam Driver could keep a straight face. As the genius architect, Cesar Catalina, Driver is the central character in the story. Head of the all-powerful Design Authority, he has a visionary scheme for a utopian city, called Megalopolis, to arise from the shambles of New Rome, the unlikely descendant of present-day New York. Certain landmarks are still intact, including the Chrysler Building, where Cesar has his office, but the urban scene is looking decidedly down-at-heel.

The mayor, Frank Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito), favours a more prosaic plan of building a big casino and a bunch of office blocks. This establishes Cicero as backward-looking and probably corrupt, while Cesar is a great idealist. Central to the architect’s plan is a new material he has discovered, called Megalon, which earned him a Nobel Prize. This mysterious substance may be used to build free-flowing organic structures, render fabric invisible or even repair otherwise fatal bullet wounds. Another startling addition to Cesar’s CV is his ability to stop time, although it’s never quite clear what’s the point of this superpower, unless we see it as a vague metaphor for the perfection of his work. After Cesar, the usual cycles of progress and decay will be arrested: his Megalon-made city will stand for all time and defy improvement.

If your head is already spinning, you’ve yet to meet Cicero’s daughter, Julia (Nathalie Emmanuel), who begins as a frivolous party girl but quickly morphs into Cesar’s muse and partner – much to her father’s horror. Then there’s Wow Platinum (Aubrey Plaza), an unscrupulous Fox News-type reporter, prepared to sleep her way to the top; Hamilton Crassus III (Jon Voight), an inconceivably rich gadzillionaire clinging to his fading manhood; and Clodio Pulcher (Shia LaBoeuf), Hamilton’s delinquent son, who likes to dress in women’s clothing and imagine himself as a fascist dictator. He also happens to be Cesar’s cousin.

There’s a host of minor characters, played by actors of the stature of Dustin Hoffman, Jason Schwartzman and Laurence Fishburn. The latter doubles as narrator, intoning ponderous introductions to ‘chapters’ of the story, announced with titles engraved in stone.

The characters’ names suggest a reference to the so-called Catalinarian conspiracy of 63 BC, in which a group of disgruntled aristocrats plotted to overthrow the elected government of Rome. It was the great rhetorician, Cicero, acting as Consul, who exposed the plot and executed conspirators. In New Rome, Cesar Catalina seeks to wrest power from Mayor Cicero by dint of his eloquence and the appeal of his futuristic schemes, but he’s not fermenting an uprising.

That role belongs to Clodio, doing his best Donald Trump impersonation – if you can imagine Donald Trump with long straggly hair, wearing a diaphanous white dress. Harnessing the anger of the masses, who spend much of the film pressing dirty faces against wire fences, he seeks to wrest control of the city from Cicero, upend Cesar’s schemes, and – with Wow Platinum in tow - usurp his daddy’s financial empire.

This is the bare bones of a plot buried under multiple layers of excess and debauchery. The centrepiece of the film is a long, public wedding celebration that incorporates (literally) a three-ring circus, with clowns, acrobats, wrestlers and chariot races. The guests spend the evening sniffing coke, swigging champagne from the bottle and trying to recapture the decadence of the last days of Rome. Coppola joins in with a split screen, so we can squeeze three times the debauchery into one viewing. In the twilight of his career, the director of The Godfather and Apocalypse Now! has turned into Ken Russell.

I wish I could report this wild party was great entertainment, but like everything in this film, it’s total chaos and goes on for too long.

One of the big problems is a lack of characterisation. Cesar, the hero of the story, is an unsympathetic creation – cold, arrogant, privileged, given to self-destructive drug binges and maudlin fantasies about his dead wife. A genius who lauds his superiority over puny mortals, it’s difficult to imagine Cesar driven by an idealistic desire to make New Rome a paradise for every human being. He seems to be a member of the human race only by default.

When Cesar recites Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” soliloquy at a political rally, it’s possibly the most pretentious moment in a highly pretentious film. His aloofness stands in stark contrast to the lunatic villainy of Clodius and Wow, who appear to have based their roles on the excesses of Elagabalus, Caligula and Messalina.

Regarding the love story of Cesar and Julia, as a flight of passion it never gets off the tarmac. The same might be said about Clodius’s attempted takeover, which is over almost as soon as it begins. For such a long film, every major plot development seems rushed and truncated, in favour of passages of banal philosophising or subplots that add little to the narrative. Russian space junk falls on the city but is quickly forgotten. A string of propositions about “time” sounds as profound as a shopping list.

Megalopolis is described as “A Fable” in the opening titles, although it might be better seen as a heavy-handed allegory about the United States today – the last ‘chapter’ title even includes the date 2024 in Roman numerals. The craziness and division of the Trump era has led Coppola to think of the last days of the Roman Empire, but the cloaks and togas make the story into a vast, bloated cartoon that never questions New York’s role as centre of the universe, or the lowly status of the working classes, who are manipulated for good or evil.

Ultimately, this Roman orgy of a film boils down to a very simple proposition. There are alternative paths to the future: the violent, dystopian world threatened by Clodius/Trump; the grimy community of small-scale patch-ups and local politics, represented by Cicero; or the utopian vision of Cesar, with its magical buildings and a garden for everyone. Coppola never makes it clear how Cesar will achieve this miracle, but he urges us to put our faith in science and human ingenuity, to dream big and aim for the stars. It’s a remarkably optimistic message from a filmmaker who clung to his own dream project for forty years, only to end with a cinematic catastrophe.

Megalopolis

Written & directed by Francis Ford Coppola

Starring: Adam Driver, Nathalie Emmanuel, Giancarlo Esposito, Aubrey Plaza, Shia LeBeouf, Jon Voight, Dustin Hoffman, Talia Shire, Laurence Fishburn, Jason Schwartzman, Kathryn Hunter, Grace VanderWaal, Chloe Fineman, Isabelle Kusman

USA, M, 138 mins

Published in the Australian Financial Review, 6 October, 2024