One morning last year in New York City, a queue formed at the entrance to the David Zwirner Gallery. As the day progressed, the line grew longer and longer, until it extended around the block. The occasion was the opening of a commercial exhibition by Yayoi Kusama, and the chance to spend 30 seconds in a new ‘Infinity Room’, surrounded by mirrors. It was the selfie-magnet of the season.

Kusama has a track record in NYC, but when she was chosen to represent Japan in the 1993 Venice Biennale, she was viewed by some as a has-been, by others as a lunatic self-promoter whom the mandarins of the artworld would never take seriously. Eighteen years later, at the age of 95, she is almost certainly the world’s most popular living artist, and museums are clamouring for shows. She has attracted huge crowds in Asia, the United States and Europe. In December, the National Gallery of Victoria, will be hosting one of her largest-ever surveys.

The NGV’s Curator of Asian Art, Wayne Crothers, promises more than 180 works, encompassing eight decades, the earliest made at the age of nine, the latest created this year, from the mental institution where the artist has resided for more than 40 years. Nowadays Kusama rarely leaves the clinic, which she entered voluntarily when she felt unable to cope with the pressures of everyday life. It has allowed her to work continuously, with no distractions. For years she has had no time or willingness to do interviews, speaking with only a handful of people, with art dealer, Hidenori Ota, acting as her main conduit to the world.

“She calls every single day,” Ota says, “sometimes many times a day, and I go to the hospital two or three times a week.”

The NGV show has been five years in preparation, and Crothers – whose brief was to be “really ambitious” – can make the rare boast that it was entirely initiated by the gallery.

“We didn’t want to simply show the pumpkins or the Infinity rooms, which are the works everybody knows,” he says. “We thought it was important to tell the human story – her childhood in Matsumoto, her early exhibitions, her obsessive desire for fame, her correspondence with Georgia O’Keeffe… it’s all about modern art, but it’s also an amazing social story, about a Japanese woman from a regional town who went through many different experiences and personality-building trials, and eventually conquered the world.”

There will be no shortage of spectacle in this story of Kusama’s life, with ten immersive installations, the greatest number ever assembled. This includes a reconstruction of her first major environment - Infinity Mirror Room - Phalli’s Field, originally made for a commercial gallery in New York in 1965. A famous photo shows Kusama dressed in a red jumpsuit, spreadeagled on a field of soft white phallic shapes covered in red polka dots, her reflection multiplied by the room’s mirrored walls.

She would not make another mirror room until 1998, and that piece will also be in the NGV exhibition, along with a room dedicated to pumpkins, and a new Infinity Room made specifically for this show. The scale of the exhibition is of particular pride to NGV director Tony Ellwood. “It’ll be the most immersive Kusama exhibition that’s ever been mounted,” Ellwood says. “It’s a hugely ambitious effort, not to mention a logistical feat.”

Kusama’s “human story” starts in Matsumoto, an historic town in Nagano prefecture, nestled at the foot of the Japanese Alps. Today it’s a busy tourist destination, but when Kusama was growing up in the 1940s, it was a conservative, provincial outpost. She held her first important solo exhibition there in 1952, at the age of 23, showing more than 200 pieces. In the late 1960s she would shock the town with her ‘shameful’ behaviour in New York and was allegedly removed from her high-school yearbook.

Nowadays she is Matsumoto’s Number One daughter and greatest drawcard. The City Museum of Art has a massive permanent display of her work, including a huge tulip sculpture in the forecourt and red polka dots plastered on the front of the building.

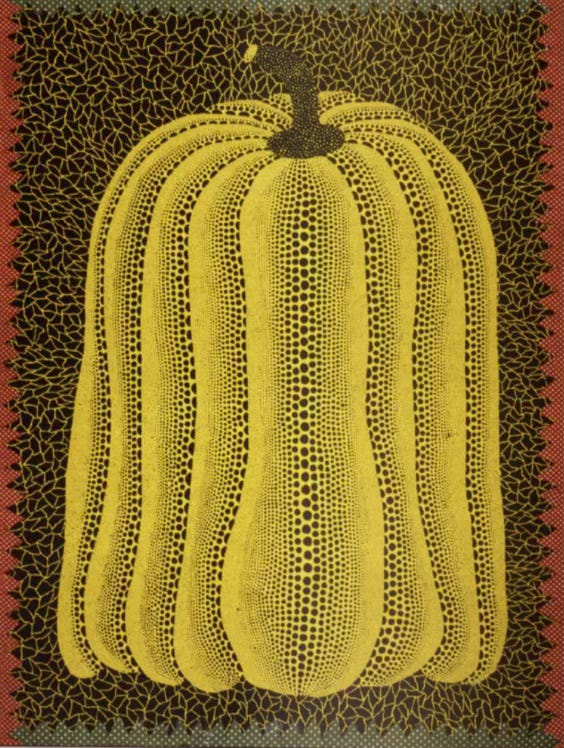

Conflicts with her mother and father, and the first signs of her chronic mental issues, fuelled Kusama’s desire to get away from the town, and eventually from Japan. Many of her signature motifs were born in Matsumoto, notably the pumpkins, which came to her as a hallucination, and the polka dots that swam in front of her eyes, threatening to “obliterate” reality.

It may have been a symptom of a narcissistic, obsessive-compulsive personality, but few artists of any era could match Kusama’s drive for self-promotion. When she arrived in the United States in 1958, she was determined to become a world-famous artist - a monumental task for a woman, let alone a Japanese woman, at a time when American art was overwhelmingly masculine. She would make her mark with a series of Infinity Net paintings that saw her cover large canvases with repetitive loops of paint, working relentlessly, sometimes for sessions of more than 50 hours. The largest of these paintings was ten metres long.

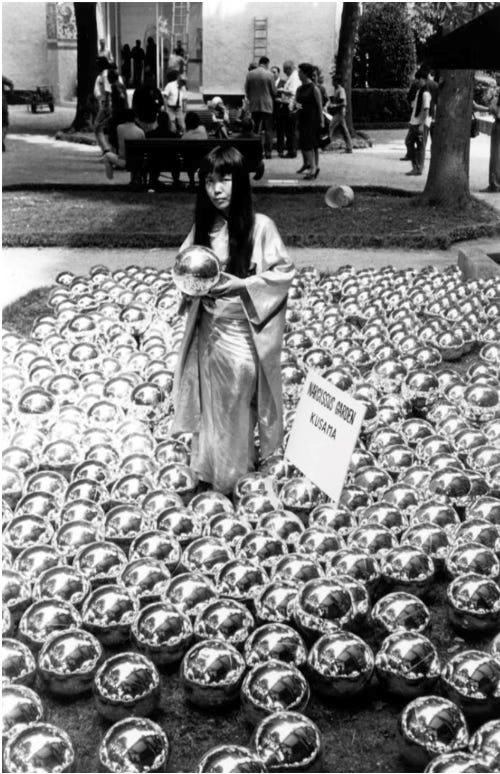

By 1962 she was toiling just as furiously on her Accumulations – objects such as chairs, tables, and even a rowboat, covered in soft protuberances. She also stage-managed a series of photographs in which she posed naked with the works. The notoreity she acquired would lead to more extreme gestures, notably an epic series of Happenings, in which nude models would perform in public, as a protest against the Vietnam War or other hot-button topics. She hosted gay marriages decades before they would become permitted by law, started her own fashion label and published a magazine.

Although she was a proponent of free love who referred to her happenings and body painting sessions as “orgies”, Kusama herself was famously chaste. She appeared as the mistress of ceremonies fully dressed and spoke often about her fear and hatred of sex. At the same time, she made every effort to exploit her doll-like looks, playing the exotic oriental in a golden kimono.

As the 1970s loomed, Kusama had worn out her welcome in New York, having exhausted audiences, who viewed her as a sensationalist who would do anything for a headline. She returned to Japan, intending to create a series of nude performances, but found it was impossible, and angrily declared her homeland to be “a fourth-class country.”

Nevertheless, by 1973 she was based in Tokyo again, and by 1975 would be hospitalised, as her life-long mental disturbances became crippling. Two years later, she had settled into the clinic permanently, and began to work with renewed vigour, no longer having to worry about the necessities of life.

It was a survey of her work at the Centre for International Contemporary Art in New York in 1989 - drawing attention to the ground-breaking nature of her early work - that sparked her rise to prominence. Ten years later these works were being celebrated by a more prestigious survey, Love Forever: Yayoi Kusama 1958-1968, that travelled to Los Angeles, New York, Minneapolis and Tokyo. When the Venice Biennale set the seal on her newfound celebrity, she had finally achieved the fame she had been seeking her entire life, a fame that continues to grow.

A key figure in Kusama’s revival was Akira Tatehata, who organised the Venice pavilion in 1993, and now serves as Director of both the Yayoi Kusama Foundation and the museum devoted to her work, located across the road from the clinic. Australians may know Tatehata as the prime mover of the landmark Emily Kame Kngwarreye exhibition that travelled to Osaka and Toyko in 2008. He jokes that he is somewhat of a specialist in “old lady genius artists.”

The 77-year-old Tatehata is a poet, curator and an enthusiastic advocate for the artists he admires. He says that when Kusama returned to Japan in the mid-70s, she had a reputation as “the Queen of scandal”, but after visiting a solo show in a very small gallery in Tokyo, he became a convert. “Even though I was still in my twenties and quite unknown,” he recalls, “I decided it was my duty to re-estimate her in Japan and the world. When I became a curator at the National Museum of Art in Osaka, I persuaded all my colleagues to admit she’s a genius.”

Although Tatehata is aware that people see Kusama as “a crazy person”, he thinks she needs to be viewed as “an authentic artist” rather than an outsider.

“She comes out of Japanese culture but doesn’t want to talk about it. For me, she’s an orthodox modernist whose work lies somewhere between Pop Art and Minimalism. She denies the elemental gestures of Abstract Expressionism but has a distinctive touch.”

For Tatehata, the key to Kusama’s art is repetition, her unique ability to return to the same motifs again and again. “It begins with the dot pattern she saw when she was seven or eight years old,” he says. “These dots keep recurring, appearing and disappearing, depending on her state of anxiety. She focuses on her fears in order to overcome them. It’s an instinctive thing, a kind of self-therapy. For the public it comes across as an obsession, and there’s something disarming about that. Obsession feels whole-hearted, it brings people together, making them feel they want to be part of whatever she is doing.”

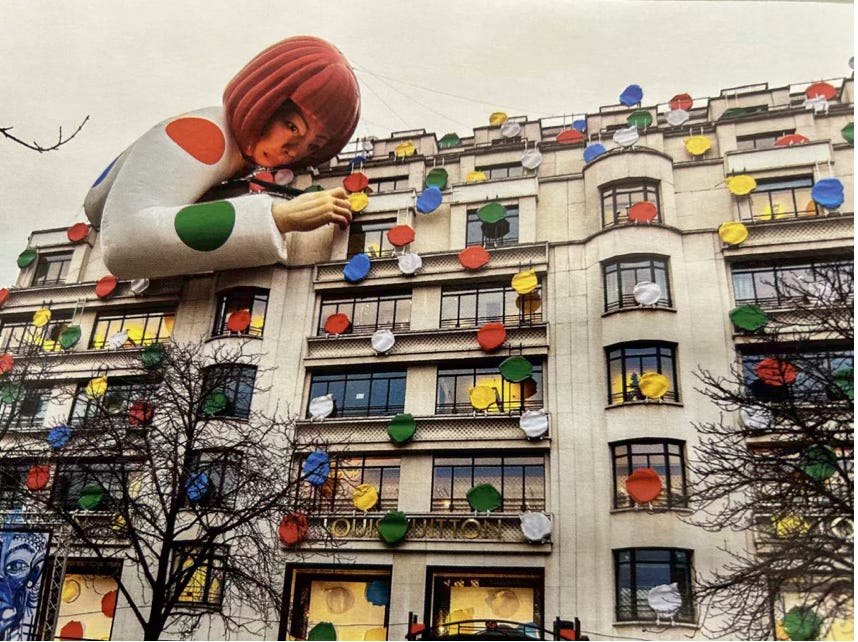

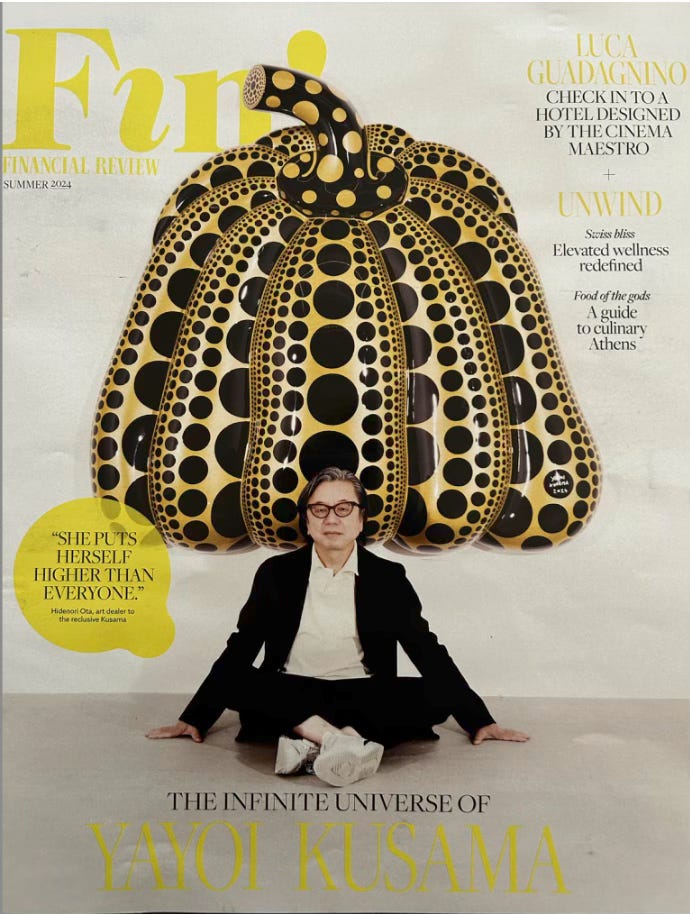

Along with critical and institutional success, Kusama has become a booming commercial enterprise. In 2022, she was second only to David Hockney for sales of work made after 2000, bringing in US$62 million to his US$75 million. To this one must add revenue from merchandise, such as T-shirts, dolls, toggles and toy pumpkins, and her lucrative collaboration with Louis Vuitton, which has plastered her trademark dots onto handbags, sneakers, overcoats, pyjamas, bikinis, and anything else that can be worn or carried. In 2022 the brand erected giant statues of Kusama applying her dots to Harrods department store in London and the Louis Vuitton flagship in Paris.

While Kusama’s work has been sold by many of the world’s leading art dealers, including David Zwirner and Larry Gagosian, her “mother gallery” is Ota Fine Arts, with branches in Tokyo, Singapore and Shanghai.

Hidenori Ota, who says he likes to stay in the shadows, has been working with Kusama since 1994, when she suggested they go into business together. He met her in 1987, when she was showing at Tokyo’s Fuji TV Gallery, and he was a young assistant to the director. A year-and-a-half later he had left the gallery, she rang and told him she’d had a fight with the Fuji TV people and proposed a partnership.

In the first few years, Ota says they would make an annual loss of US$40,000, with Kusama providing the capital. But she never had any doubts about her eventual success. “She believes she’s always been important,” he says. “She’s not at all surprised at the way she’s regarded today.”

One thinks of an earlier interview with Tatehata, where Kusama says: “The first thing I did in New York was to climb up the Empire State Building and survey the city. I aspired to grab everything that went on in the city and become a star.”

The relationship between the artist and her dealer has endured and prospered, although it’s not always easy. “She calls every single day,” Ota says, “sometimes many times a day, and I go to the hospital two or three times a week. Last Sunday I was in Beijing and she called me several times. In the first call she said: ‘Ota-san, bring back those paintings you took from me yesterday!’”

“I said, ‘No, no. I wasn’t in Tokyo. I’m overseas.’ But she believes I took many paintings from her to sell and make money. Then she says: ‘You didn’t send me any money for a year,’ and screams at me. But two hours later she calls again, and very gently – like a little girl – says: ‘Ota-san, the next time you come to the hospital please help me find my red dress.’”

Has it always been like this? Almost thankfully, Ota reports that Kusama’s prodigious energy is decreasing with age. “Now there are only small explosions. Ten years ago, there would be big explosions.”

Paranoid, egocentric, supremely self-confident, Kusama – once a pariah in her own country – is now popular with everyone. “All the generations from young to old,’ says Ota, “on every continent.” She insists on her own exceptionalism, not wishing to be pigeon-holed as a representative of any particular style or claimed as a feminist icon. According to the dealer, she will not allow herself to be compared with any other female artist in Japan. She puts herself higher than everyone.”

Or as she once said: “Ota-san, remember, I’m John Lennon. I’m not Yoko.”

Yayoi Kusama, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne,

15 December 2024 - 21 April 2025

Published in the Australian Financial Review, 12 October 2024

John McDonald flew to Tokyo courtesy of the National Gallery of Victoria